Finns and the Saami— Rich shamanic traditions.

Home » Articles and News » Finns and the Saami— Rich shamanic traditions.

by Leppä (Harold Alden)

From prehistoric times in Finland there were two indigenous peoples—the Finns and the Saami—and both developed rich shamanic traditions.

From prehistoric times in Finland there were two indigenous peoples—the Finns and the Saami—and both developed rich shamanic traditions.

At the same time, the documentation regarding Finnish shamanism is fragmentary and the subject of various debates. This is much less the case for the Saami, who in contrast to the Finns maintained their original shamanism well into the historical period when it was more easily and completely documented.

Where conclusive evidence is lacking on particular points, the following account of the shamanism of the Finns will rely on the informed opinions of influential scholars.

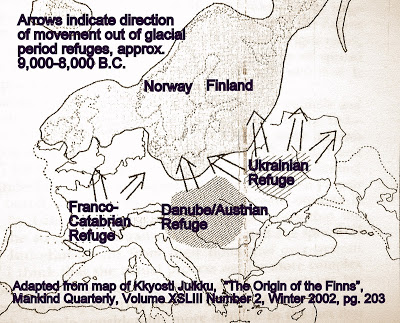

One area of considerable agreement among scholars is that the Finns and Saami have continuously settled Finland since at least 9,000 B.C. (Julku, 2002; Makkay, 2003; Niskanen, 2002; Nuñez, 2002; Saukkonen, 2000; and Wiik, 2006).

The large icecaps of the Würm glaciation covering much of Europe in 23,000 B.C. began to recede in10,000 B.C. During the long glaciation period European population groups had clustered in three large refuges: the Franco-Catabrian, the Danube/Austrian, and the Ukrainian.

Figure 1 Movement Out of Glacial Refuges

The Proto-Saami people originated in the Franco-Catabrian Refuge. In 9,000 B.C., and perhaps even as early as 13,000 B.C., they moved northward, pursuing deer north across the dry North Sea bottom between the British Isles and Denmark and up the ice-free coast of Norway.

About 8,000 B.C. the melting of the icecap progressed sufficiently for them to travel as far south as the Baltic Sea, where they encountered the Proto-Finns. During the millennium or more of their northern refuge they likely had contacts in various directions and developed a shamanistic culture closely resembling those of other peoples of the pan-Arctic zone, e.g., the Inuit of Canada.

Below is an ancient Saami shaman drum in the collection of the National Museum of Finland.

Figure 2 Saami Shaman Drum

The Proto-Finns likely originated in the Ukrainian Refuge, together with other Proto-Finno-Ugric/Uralic speaking peoples. They followed the retreating icecap northward, reaching the Baltic and southern area of Finland in 9,000-8,000 B.C. (See map above.)

In southern Finland the Proto-Finns developed a shamanic hunting-gathering-fishing culture very similar to those of peoples across the sub-Arctic Eurasian forest zone, exemplified in the classic shamanism of the Evenks of Siberia.

An Evenk shaman from the early modern period is pictured below.

Figure 3 Evenk Shaman

The word “saman” was originally derived from the Tungus language of the Evenks, often defined as meaning “one who knows.”

The shamanic complex in common across the sub-arctic forest zone included a soul which can move freely outside the body, the alliance of shamans with helper-spirits, the ability to shape-shift, and the journey to the Otherworld while in a trace state. (Siikala, 2002b).

One of the first forms of Proto-Finnish shamanism was represented in the Mesolithic Suomusjarvi culture of Finland, 8,300-5,000 B.C. The historian Eino Jutikkala writes:

“The people of the mysterious Suomusjarvi culture may also have left a trace of themselves, in the form of shamanism, on the world of belief depicted in the Kalevala runes. And because there was never complete break in settlement, and the populace never died out to the point of having no descendants, there should yet live, in Finnish genes as well, traces of the legacy of these people from nine thousand years ago.” (Quoted in Pentikäinen,1999)

The Proto-Saami and Proto-Finnic peoples came into contact in the Neolithic period and joined together in the Comb-Ceramic Culture (5,000-3,200 B.C.) that had diffused from the east to the Baltic Sea area. A reconstruction of the type of settlement characteristic of the Comb-Ceramic people is pictured below.

Figure 4 Comb-Ceramic Settlement

The shamanic heritage of the Comb-Ceramic Culture is on display in their rock paintings, of which there are currently more than 100 identified sites in Finland.

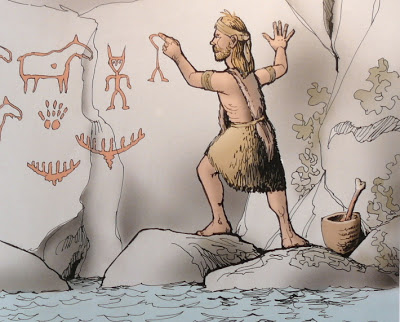

The following illustration from a children’s book about Stone Age Finland portrays what could be a shaman using an iron oxide mixture to create paintings on a rock face along a waterway. (Photo from Purhonen and Miettinen, 2006)

Figure 5 Creating Rock Paintings

The rock painting below is from Juusjarvi Lake near Helsinki. It is thought to depict a shaman falling into trance accompanied by a fish spirit helper, possibly a pike.

Figure 6 Juusjarvi Rock Painting

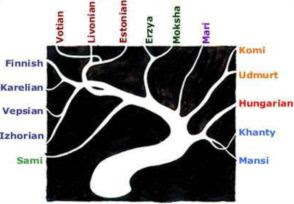

The Finns and Saami began to diverge as distinct ethnic groups at the end of the Comb Ceramic period in 3,200 B.C., speaking Finno-Ugric languages. Other Finno-Ugric ethnicities and languages that emerged at this time included those of the Estonians, Karelians, and Hungarians.

Figure 7 Finno-Ugric Languages

Beginning about the year 3,200 B.C. the Indo-European Cord-Ceramic and Boat-Axe Cultures arrived in the Baltic area, including Finland. They brought with them pre-Germanic linguistic and cultural influences and early agricultural practices.

Over time the Finns, while still maintaining their Paleolithic hunting and fishing culture in the Finnish interior, began cultivating land in the south of Finland. In doing so they geographically displaced the Saami population to the north, sometimes with force as in later history through so-called “secret or surprise wars”. (Pentikäinen, 2002)

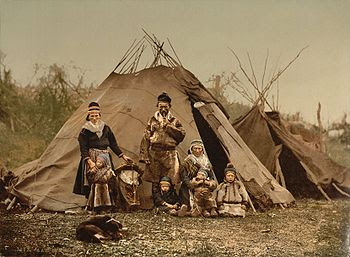

The Saami maintained their distinctive shamanic practices based on a hunter-gatherer subsistence mode relatively unchanged from the Bronze Age (dating from 1500 B.C.) until the 19th century, when churches had confiscated the last of their sacred drums. There is evidence that Finns periodically consulted on and borrowed from Saami shamanic practices and implements across that entire span of time.

Even today the Saami maintain an active shamanic culture with clear links to their ancient practices.

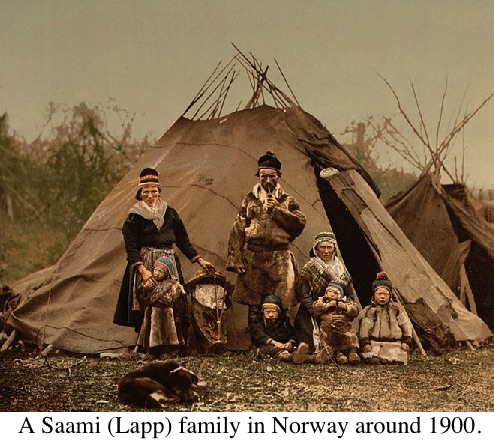

The following is a picture of a Saami family in Norway in 1900.

Figure 8 Saami Family

The Baltic Finns maintained their shamanic culture relatively unchanged through the Bronze Age (1500-500 B.C.) and into the Iron Age (500 B.C.-0). During this time the most common shamanic activity of both the Finnish shaman, or noita, and Saami noide was healing. According to DuBois (1999), as late as the Viking Age (800 B.C.-1025 A.D.) the Finnish and Saami shamans:

“…battled against instances of either soul loss (when the patient’s soul became stranded in some otherworld) or soul intrusion (in which a foreign soul invaded the patient’s body).” They relied on “ecstatic trance and the accompanying spirit journeys….to rescue souls, discover the etiology of a disease, or find out details useful in controlling an entity’s activities (e.g., its secret name or origin).”

During the Bronze Age and especially the Iron Age there began to arise among the Finns a new type of religious specialist suited to an increasingly settled agricultural people: the tietäjä (literally “knower” or “sage”). Gradually this new practitioner replaced the noita of an earlier era.

A principal difference between this practitioner and the noita was in the multiple roles and specializations the tietäjä took on in the new more complex proto-agricultural society: healer, diviner, judge, name-giver, and spokesperson.

As well, rather than relying solely on shamanic trance journeys to Otherworld spirit helpers as in earlier times, the tietäjä also used the singing of runes to achieve altered states and promote healing and other objectives. Runes are magic songs or incantations in a distinctive poetic metre, some of which preserve themes of the pre-historic shamanic Finnish past. According to Dubois, at least some of the magic incantations may owe their composition to the early noitas.

From the Bronze Age well into the 19th century runes were passed down orally in a continuous folk tradition.

Among the runes are epic poems detailing the exploits of shamanic figures from prehistory such as Väinämöinen and Ilmarinen. In the 18th century many of these epic poems and magic incantations were collected by Elias Lönnrot and others. Their sources were tietäjäs as well traditional rune singers who had memorized large numbers of the poems and performed them at in private and at public occasions in tandem, as pictured below. Lönnrot published a selection of the runes in a synthesized form in the national epic, the Kalevala.

Figure 9 Rune Singers

In addition to the shaman’s drum, tietäjäs used the wooden stringed instrument similar to a zither, called a kantele, which also dates from the Bronze age, to achieve shamanic altered states. The following photo of a kantele being played is by I.K. Inha from 1894.

Figure 10 Playing the Kantele

The following description from the 18th century indicates that the tietäjä continued to be able to make spirit journeys to the Otherworld while in a trance state, preserving the link to the Eurasian shamanistic complex:

“Sitting on stones, tietäjät were said to pass over rivers and lakes and their spirits, separate from their bodies, were said to travel to other remote places obtaining knowledge and after some time reuniting with their bodies. They prepared for such spiritual journeys by quietly humming a magic poem, from which they feel into a trance (“slipped into the crack”) and while the spirit was traveling by itself, the body, like a lifeless body at least, lay as if dead, to recover again after the spirit’s return from its journeys.” (Siikala, 2002a)

The culture of the tietäjä also retained the animism of the Eurasian shamanic complex. Comparetti wrote in 1898:

“In the last analysis we find that the original and proper character of Finnic mythology is that which distinguishes shamanic belief, or generally speaking, that which is called animism….The world, according to the Finnic idea, is quite peopled with spirits; everything has its haltia, every tree every hill, every lake, every waterfall, etc.”

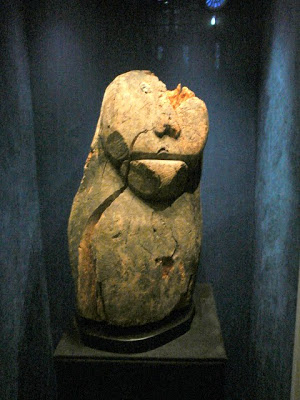

The wooden statue below from the collection of the National Museum of Finland is of a fish god from the Lake Ladoga region.

Figure 11 Fish God of Ladoga

Laura Stark says of the position of tietäjäs in the 18th and 19th centuries:

“The tietäjä was more than a master craftsman…. Although tietäjäs were not religious or spiritual leaders in their communities, they nonetheless tended to command respect and authority based on their knowledge, competence and an inner supernatural force known as luonto.” (Stark, 2006)

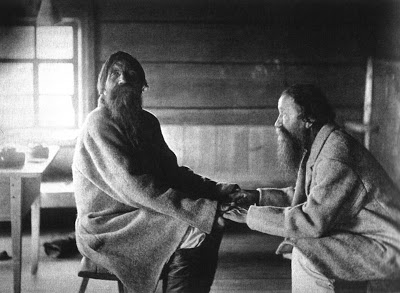

In the picture below from the early 20th century the tietäjä Miron-Aku reenacts the ritual of transmission of the powers of a tietäjä to an apprentice. (Photo from Siikala, 2002a)

Figure 12 Transmitting Tietaja Powers

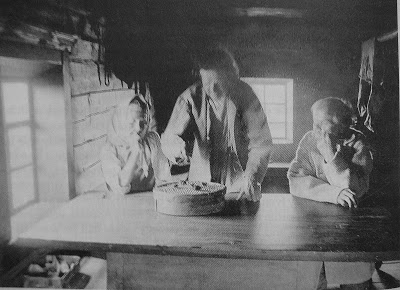

Owing to rural isolation and lack of penetration by the church, the tradition of tietäjäs as seers and diviners persisted relatively unchanged for millennia in the Savo region of Finland. The 1894 photo by I.K. Inha (Siikala, 2002a) shows a Savo tietäjä using the movement of objects on a sieve as a means of divination, recalling both the shape of the shamanic drum used in earlier times by Finns and the well-known drum divination technique of the Saami.

Figure 13 Divining with a Sieve

Despite centuries of hostility from the Catholic and Lutheran Churches, (witch trials, destruction of texts and sacred sites such as sacred groves, banning of rune singing) the tietäjä tradition continued as late as into the mid-20th century in some rural areas of Finland. Today, several organizations and a number of individuals continue to practice and support the shaman/noita/tietäjä tradition in Finland. Their work will be the subject of future posts on Spirit Boat.

There is evidence that the classic tietäjä tradition continued as late as the 1970’s in Canada. According to Matt T. Salo, Finnish immigrants took the tietäjä tradition with them during the periods of mass emigration to the United States and Canada in the early twentieth century. Salo, an anthropologist from Northern Illinois University, wrote that there still was a viable tietäjä tradition among Finnish immigrants in in the Sudbury, Ontario area of Canada at the time of his field research in the early 1970’s. (Salo, 1973)

Salo says “To some extent practices based on the magic world view were…transported to the New World with early immigrants. One such complex of beliefs here referred to as the tietäjä tradition, is based on the ancient practice of shamanism and still finds expression in the roles of the folk healers recognized among the Finnish settlers in northern Ontario.”

Salo details from his field research a variety of examples in which rural people consulting local tietäjäs and other folk healers in one or more of their roles: seer, magician, diviner, bloodstopper, bloodletter, bone setter, midwife, cupper, herbalist, or maker of medicines. In one example Salo describes what he calls a “healing drama little changed from the shamanic ritual practiced for millennia in the forests of northern Eurasia before being transplanted to Canadian soil.”

Some people had come to Canada already trained in these skills. For example, one individual near Sudbury was direct heir and former apprentice of Kyyran Jussi, a famous tietäjä in Finland. Others had learned the skills from other immigrants, relatives or friends.

Salo says that in general, the tietäjä tradition was embraced by those who were already familiar with it in Finland, generally first generation immigrants. He notes that there was considerably less interest in the practices among second and third generation Finnish-Canadians, suggesting that today nearly 40 years later, probably few remnants of the original tradition still exist.

About the Author:

Leppä (Harold Alden) resides in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Shamanism, Buddhism, astronomy, paleontology.

His blog Spirit Boat – Exploring Finnish shamanism.

Home » Articles and News » Finns and the Saami— Rich shamanic traditions.